Rent Control Has Been Eased, Will GTA Rent Growth Follow?

By: Diana Petramala, Candace Safonovs, and Alex Butler

December 7, 2018

The Toronto Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) rental market saw two major news items in the last few weeks. CMHC released their annual rental report last week, which provided an update on developments in rents and rental supply in 2018. As well, the Ontario Government announced that it was removing rent control from units built after November 15, 2018.

This blog provides an update on the rental market and our expectations for rents under the new rent control change.

Renting is out of reach for the average household

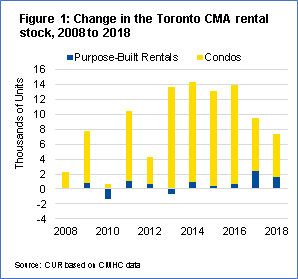

The supply of new rental accommodation in the Toronto CMA grew by 7, 308 units in 2018, the smallest increase since 2012 (Figure 1). Almost 80% of these new units came from the condo market, as private investors rented out their units. Units in new purpose-built rentals rose by just 1,616 in the last year.

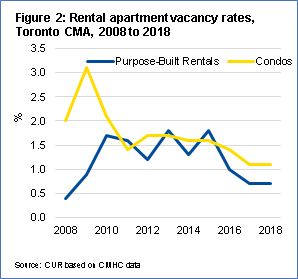

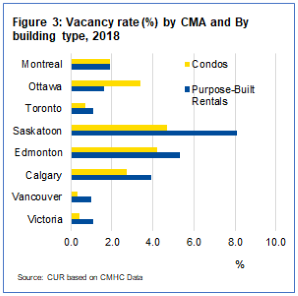

Overall, the stock in the rental market grew just enough to keep pace with demand in 2018 and the vacancy rate held steady – albeit it is sitting at a very low rate. Historically, a market has been considered balance if the rental vacancy rater was 2% or greater. The October 2018 vacancy rate was 1.1% for purpose-built rentals and 0.7% for rentals in condos, signaling tight market conditions. The only other major CMAs to have such low vacancy rates across Canada were Victoria and Vancouver (Figure 3).

With vacancy rates so low, demand pressures have led to high rents. Average rents in the Toronto CMA rose by 4.7% year-over-year in the purpose-built rental market (to $1,307), and by 5.5% on condos (to $2,235), in 2018.

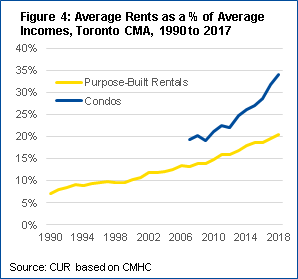

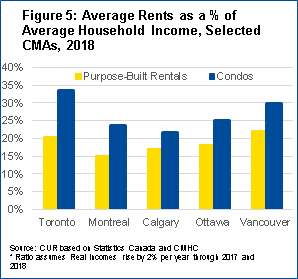

Rents as a percentage of average household incomes have been climbing steadily since 1990. The metric for affordability is that gross rents do not surpass 30% of a household’s pre-tax income. By this measure, the average existing purpose-built rental still remains affordable. However, the rents for condos rose above 30% of income in 2018 (Figure 4). Rentals in the condo market are unaffordable to the average household in the Toronto CMA. The majority of the new rental stock being added to the market on an annual basis is unaffordable to average households. Toronto is the only large CMA in Canada where this is the case. Condo rentals in Toronto are even more expensive than in Vancouver, both on an absolute basis and relative to household incomes (Figure 5).

There is a risk that supply constraints continue to put upward pressures on rents, at least in the short-term. In a recent UrbanOutlook webinar, Urbanation, an information provider for the development industry, noted that while rents currently average $3.50 per foot for condos, investors buying pre-construction would now require a rent of $5.36 per foot by 2022 – an increase of almost 50% in rents. Urbanation did note that a large number of condos are currently under construction and that the completion of these units might help bring the market closer to balance. However, until that happens, rental rates are likely to skew upwards.

Easing rent control on new construction a step in the right direction, but other supply measures needed…

In the spring of 2017 the Liberal Government expanded Ontario rent control rules to apply to the entire rental universe. This includes purpose-built rentals, condo apartments and secondary suites. Prior to April of 2017, rent control had only applied to purpose-built units constructed before 1991. In its Fall Economic Statement, the current Progressive Conservative Government partially reversed the Liberal’s decision by excluding rental units built after November 15, 2018 (the day after the statement was released) from rent control.

It is important to note that Ontario has had a vacancy de-control regime since 1975, meaning that when a rent control unit becomes vacant, a landlord can charge whatever the market will bear. So, will removing rent control further exacerbate rents?

Rent control in its current state will support current renters, and will keep their rents growing at a stable pace as long as they don’t move. In theory, removing rent control on new units should encourage modestly more investment in the rental stock over the long-term.1

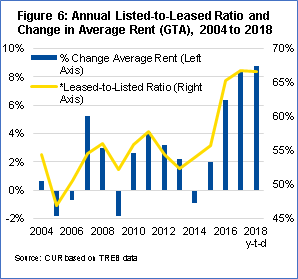

In the meantime, however, the evidence shows that new renters (such as newcomers and millennials) face increasing rents. Figure 6 shows data on rentals listed on the Multiple Listing Service (MLS) system. The average going rate for rent on these units has been rising by almost 9% per year for the last two years. The policy of vacancy de-control has meant that renters new to the market are not shielded from upward pressures on rents.

This figure also suggests that the best way to keep rents under control is to increase supply of rental units. The leased-to-listed ratio is the number of units being rented through MLS (demand) as a share of the number of units available to be rented (supply). The chart shows that the fewer units available relative to demand, the bigger the rise in rents faced by households moving into them. Rent growth on units listed on the MLS remains near 2% when the leased-to-listed ratio hovers between 50% and 55%, but grows rapidly for a ratio greater than 55%.

The good news is that the Conservatives have stated that they will be launching supply side initiatives to stimulate supply for both rental and owner households – beginning with a Housing Supply Advisory Council.

In the immediate future, unlocking the potential of secondary suites is low hanging fruit on which the government can focus. The cost to construct a secondary suite in an existing home is about $55,000, compared to almost $250,000 to construct a basic condo not in a central location.2 The rent on a secondary suite is approximately $1,000 a month, compared to rents on condo which run close to $2,000 per month. Policies to support and encourage homeowners to build secondary suites could prove a relatively affordable and effective way to create affordable rentals.

________________________________________________________________________

(1) Jan K. Bruechner (2011). Lectures on Urban Economics. MIT Press, Cambridge Massachusetts and London UK., pp. 141-143.

(2) Altus Group, City of Mississauga, CMHC & N. Barry Lyon Consultants

Diana Petramala is Senior Researcher at Toronto Metropolitan University’s Centre for Urban Research and Land Development (CUR) in Toronto.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________