A snapshot of African history in photographs

The Way She Looks: A History of Female Gazes in African Portraiture. Photographs from The Walther Collection (installation view), 2019 © Larissa Issler, Ryerson Image Centre.

If you haven’t seen it yet, you have until December 8 to see the exhibition The Way She Looks: A History of Female Gazes in African Portraiture at the Ryerson Image Centre (external link) . Drawn from the holdings of The Walther Collection, The Way She Looks revisits the history of African photographic portraiture through the perspectives of women, both as subjects and photographers.

The exhibition is curated by Sandrine Colard, an art historian, writer and curator based in New York and Brussels. A specialist of modern and contemporary African arts, Colard is a professor at Rutgers University-Newark and has been appointed artistic director of the 6th Lubumbashi Biennale 2019, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

She was inspired to create the exhibition as a way to re-examine the place of women in African photography.

“When I was testing this title by people, almost 99 per cent thought that I was talking about their physical looks,” Colard said. “No one understood it as the way she looked at the world or themselves or their circumstances. And for me, it was very crucial and very important because it really meant that their point of view, literally and figuratively, had never really been taken into account.”

Ryerson Today walked through the exhibition with Colard, who picked out some of her favourite images from the collection and shared her perspective on the photos.

Please note for the 19th-century works below, italicized titles are used to indicate information that has been transcribed directly from the photographic object. Some of the titles include outdated or offensive terms to describe African communities. To preserve historical accuracy, these descriptors have been maintained but are followed by [sic].

James Gribble II, Kaffir [sic] Woman, South Africa, 1880s, albumen print. Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg.

SC: When you look at this [image], she's very aristocratic. She has this gaze, you really feel her presence, you really feel her as an individual, but these women are never recognized as such. When you look at the caption, Kaffir [sic] Woman, especially now, it's a derogatory term for Black South Africans. And yet when you look at this woman, she looks completely self-possessed, in control of the way she wants to pose. And so it was, for me, it was really interesting to point that out. To show how these women, even in these circumstances, where most of the time they were not recognized as a model as you would have, still very much assert their presence and still, are in control of the way they pose.

The Way She Looks: A History of Female Gazes in African Portraiture. Photographs from The Walther Collection (installation view), 2019 © Larissa Issler, Ryerson Image Centre.

SC: We have a sample of images that really exposed the breast of the women. Those sort of typical, colonial images, voyeuristic images. I wanted only a few of them, just to give a historical perspective. But my goal here was really to concentrate on the viewpoints of women and not on the voyeuristic gaze looking at them. This one was important for me, because here you have a sort of refusal of the model towards a photographic transaction. You can feel it when you look at her expression in the way she poses, that she does not want to be in this picture. You can see that her jaw is clenched and her lips are upturned; her gaze is defiant, and at the same time she's trying not to be there. It was interesting to show that and also to pair it with another type of image that was more erotic, where the gaze is outside of the frame. We don't know if the photographer asked her to do that, to sort of titillate, or if she just looks away because she also didn't want to be there.

The Way She Looks: A History of Female Gazes in African Portraiture. Photographs from The Walther Collection (installation view), 2019 © Larissa Issler, Ryerson Image Centre.

SC: Starting in the 1990s, with photographers like Zanele Muholi, you had a generation of women who started making their own photographs. Lebohang Kganye is a South African photographer, woman photographer. And in this series, she basically takes photographs of her own mother, who had recently passed away, and she poses with the clothes of her mother, and she juxtapose digitally her own silhouette on that of her mother. And I thought it was very interesting because it's basically how textile and wearing the same clothes create that bond with the subject. And in my own research in the Congo, this is something that I found, that even in the 1930s, 1940s, women sometimes wore the clothes of a sister who had just passed away and they went back to the photographer posing with these clothes to express over death the bond that they still had. Interestingly, the policy in South Africa at the time of apartheid, they had to relocate families to another part of the country, so very often it was a way to completely dismantle families. And so for her, because her mother was the last link to her extended family, it's also a way to try to rebuild that link to her family.

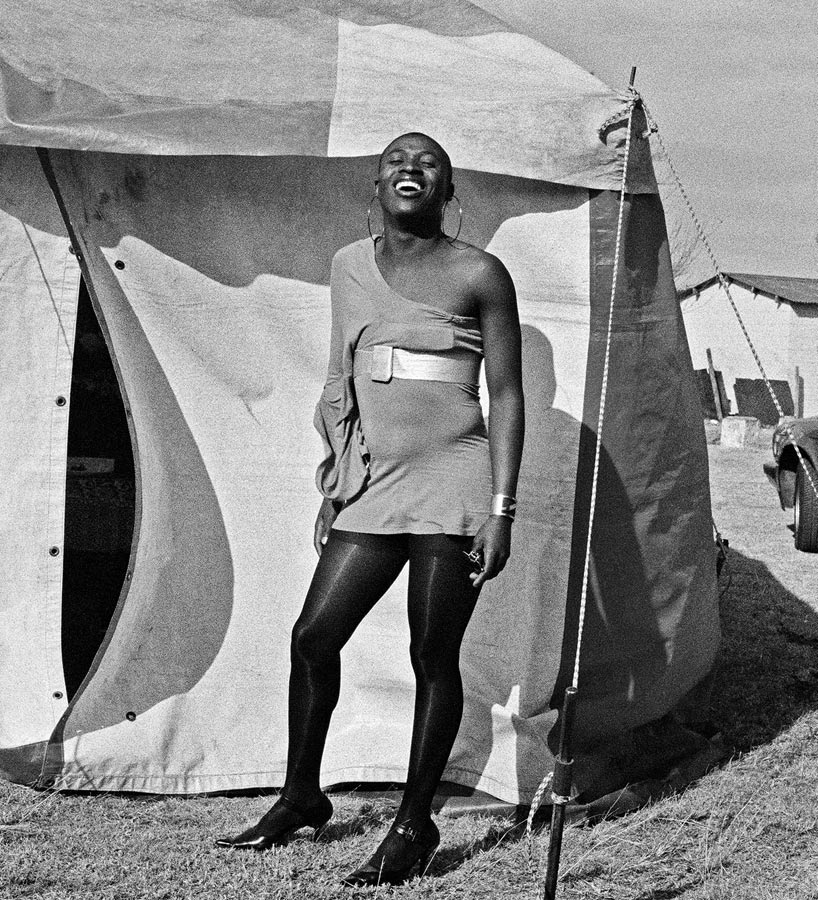

Sabelo Mlangeni, Bigboy, from the series Country Girls, 2009, gelatin silver print © The artist. Courtesy of the artist and The Walther Collection.

SC: Sabelo Mlangeni, he's also a South African photographer. And in this photograph, he's making photographs of gay and transgender communities but in the rural part of South Africa. And he's really portraying how flamboyant and in full possession of themselves, how they are enjoying their body, how comfortable and how happy, joyful they are with their body. And what was really interesting for me, is that first of all, even though the Constitution of South Africa is extremely tolerant towards gay and transgender communities and LGBTQ communities, in reality, it's an extremely violent society against these people. So it was a really moving way of portraying the resilience of these communities. This portrait resonates a lot with a very famous portrait of Miriam Makeba. She made the cover of Drum, which was a very well-known and famous Black South African magazine that was really showing how even in the condition of apartheid, Black life could be glamorous, could be joyful. And so there's a very famous photograph of Miriam Makeba posing the same way. This photograph repeats the pose that she had, with her head thrown back in an expression of joy.

Jodi Bieber, Babalwa, from the series Real Beauty, 2008, inkjet print © The artist. Courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg.

SC: [This image] was a perfect conclusion to the exhibition. I've been asked if this image was there to sort of propose, to call your gaze but really it’s irrelevant. It's an African woman, who's a photographer – Jodi Bieber – celebrating another African woman subject. The model is in her own home, she decided on the pose. But there's nothing about sexuality, desire; it's really a woman being in full possession of herself. There's a balance in this photograph between the photographer, the model, and her gaze and her body. Everything is aligned, she seems very comfortable; her body is taking over her gaze. And so it was a sort of reconciliation between what the issue and the history of African photography for women had been. It was a beautiful image to add.

Colard was awarded the 2019-2020 Ford Foundation Fellowship to write a book about the history of photography in the Democratic Republic of Congo. She was interviewed by Canadian Art (external link) and Afrotoronto.com (external link) about the exhibition.

To learn more about the exhibition, check out the Ryerson Image Centre’s new podcast, Sightlines (external link) , which features interviews with artists, activists and curators, about the importance of The Way She Looks: A History of Female Gazes in African Portraiture.

For more information regarding this exhibition and related events, please visit the Ryerson Image Centre website (external link) .