Holocaust survivor Elly Gotz brings history to life in moving testimony

In a virtual event organized by Hillel Ryerson (renaming in process), Elly Gotz shared haunting details about life under the Nazi regime, and overcoming anger and hatred in its aftermath.

CW: This article mentions antisemitism and genocide.

--

When Germany occupied Lithuania in 1941, Elly Gotz was 13 years old and had just bought a new school uniform, excited to start grade seven. He had no idea that he would never get to wear it, that he was instead about to spend the next four years in the Kovno ghetto and Dachau concentration camp, isolated from the rest of society and struggling to survive.

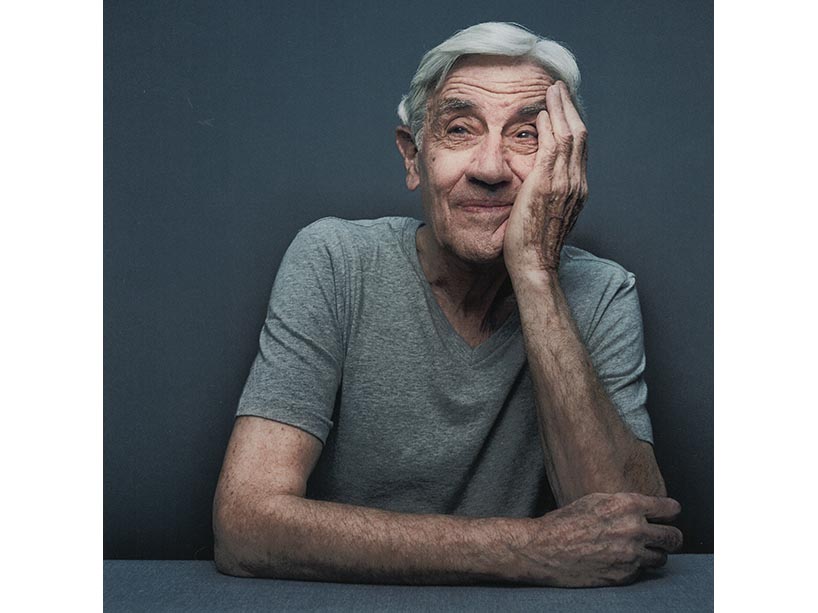

In a virtual event hosted by the student leadership of Hillel Ryerson (renaming in process) on the evening of Thursday, Nov. 18, 93-year-old Gotz shared his life’s story with the peculiar calmness and sense of humour often found in people who have known deep pain and loss.

Taking us through the very first week of the war when Jews were no longer considered citizens of Lithuania despite having lived there for more than 800 years, Gotz spoke of his time in the Kovno ghetto and the Kaufering subcamp of Dachau, his family’s journey to Norway after the Second World War, moving to Zimbabwe and ultimately making Canada his home.

The German invasion

Gotz with his mother, Sonja, in 1937. She was a nurse and worked in a hospital before the war started.

Gotz was always an excellent student who loved maths, physics and history. But even at the young age of 13, his passion was building model airplanes. He dreamed of flying a plane one day and becoming an aerospace engineer.

“I never got to attend high school. When the Germans took over, they said the Jews were the enemies of all people, they should be taken out of society and locked up separately in ghettos. In the first six weeks of the war, more than 6,000 Jews were killed in the city of Kaunas,” Gotz said. “Ghettos were created by taking old parts of town and surrounding them with barbed wire. 6,000 Catholics that lived there had to move out and 70,000 Jews moved in, forced to live in very crowded conditions. My family and I were given one small room.”

The Nazis went door-to-door and ordered the Jews to hand over their valuables. “They took everything away. The Germans were very orderly people; they wrote everything down. Every robbery, every killing, it was all documented. So, they stole our things and gave us a receipt,” said Gotz.

Life in the Kovno ghetto

Everyone in the ghetto from the age of 15 to 65 had to work as forced labour. “They told us ‘you are not getting paid; you are lucky we’re feeding you.’ But I was still 13 and didn’t have to work, so I read and read and read,” Gotz said.

He remembers one morning when the Germans announced that nobody would go to work. Instead, everyone had to come to a large field, or they would be shot on the spot. An officer sorted each person into two groups: one was allowed to go back home, the other wasn’t.

The next day, on Oct. 29, 1941, the second group was made to march up the hill towards the Ninth Fort, a military compound where German soldiers practiced shooting. 10,000 Jews randomly picked from the ghetto, including women and children, were murdered in one day, shot with machine guns and their bodies thrown in long trenches.

Gotz lost many friends and family members that day. His uncle became desperate to get his two-year-old daughter out of the ghetto, fearing that a similar fate awaited the whole family.

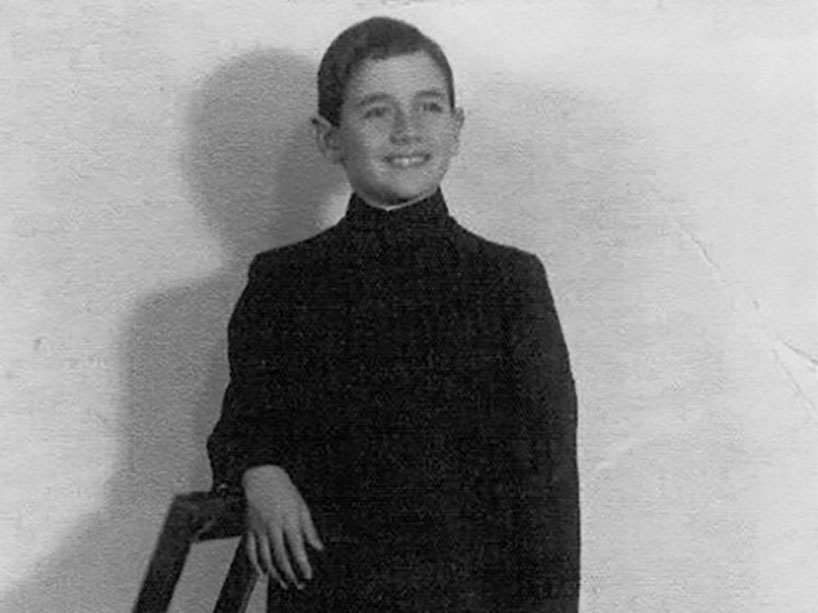

A young Mr. Gotz in the uniform he was supposed to wear to high school, which he wasn’t allowed to attend once Germany invaded Lithuania.

The little girl and Gotz were very close, with nobody but each other to spend time with. “I started to feed her, tell her stories, and she learned five new words every day. She became like my baby,” said Gotz.

Through secret letters, Gotz’s uncle arranged to have his Catholic friend’s wife take his daughter from the ghetto.

“My mother was a nurse and she gave the child an injection that completely knocked her out for a few hours. They put her in a rucksack which my uncle carried to work with 25 men and two soldiers. He left her under a tree, from where a man grabbed the bag. Later, we got a message saying the goods had arrived. Our child was safe,” Gotz recalled.

Gotz also remembers being upset about his cousin waking up among strangers, speaking a language she didn’t understand.

“But this woman took a tremendous chance. If anyone reported that she was hiding a Jewish child, she would be hanged right away,” Gotz said. “And three months after we got her out, soldiers with trucks came to the ghetto hunting for children. 3,000 children were dragged out of their homes and murdered in one day. After that, you couldn’t show a child in the street.”

The Jewish management at the ghetto asked the Nazis for permission to establish a trade school for kids from 12 to 15 years.

“I joined the metalwork school. I learned how to make keys and locks, and became a locksmith. I learned all the metal trades and became a blacksmith. I learned it for two years and enjoyed it very much,” Gotz said. “When I was 15, I graduated and they gave me a job as a teacher. I started teaching metalwork to 25 kids in the morning and 25 in the afternoon. I thought I would be a mechanical engineer.”

Gotz (standing) teaching students in the Kovno ghetto Fachschule (trade school). On his right is Itzchak Kopilowitz, with whom he reunited in Tel Aviv in 2007. Gotz accidentally discovered the photo in 1994 while visiting the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC.

One day, they were told that the Germans were liquidating the Kovno ghetto and the Jews would be taken somewhere else to work.

“We didn’t believe them. We thought they would take us up the hill and kill us too. So our family decided to hide, and if they found us we would commit suicide,” said Gotz. “We brought in two weeks worth of water and food in a storage room in our basement, and placed a heavy table in front of the door. My mother laid out syringes filled with a drug she used in the hospital, which could create a heart attack.”

Gotz went on to describe the horror of hiding in a small storage closet, his mother ready to inject her family with a deadly drug, as German soldiers searched their basement. When they finally left, the family remained in place for a number of days, fearing their return.

They eventually ventured out of their hiding place and saw a train outside the ghetto gates. Unsure where they were headed, the Gotz family managed a narrow escape. The ghetto was burned down shortly after the train departed, all remaining Jews killed.

At the end of his three years in the ghetto, Gotz was one of only 8,000 Jews who survived in the city of Kaunas out of the roughly 35,000 who lived there before the war.

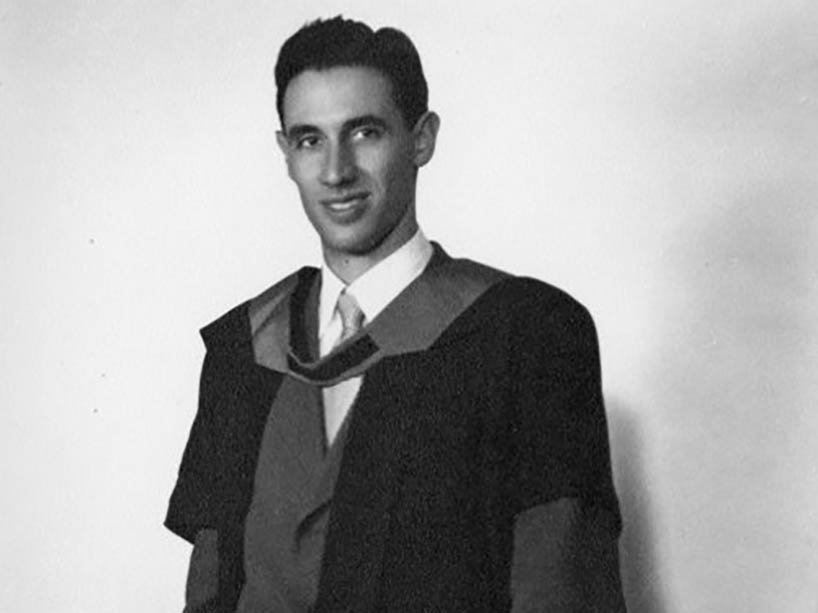

Gotz was separated from his mother after leaving Kovno, as the men and women were put in separate concentration camps. Once the war ended, the family was reunited and they moved to Norway, where they are pictured here.

Terror at the Dachau concentration camp

The overnight train journey saw 200 people jammed together with no water, food, air or facilities. When the train stopped, people had to walk over dead bodies; the men and women being divided into separate camps. Gotz didn’t get to say goodbye to his mother.

“Dachau was established by Hitler in 1933 for his political enemies. It was the first and the biggest camp at the time. It was surrounded by two rows of barbed wire and had machine gun posts in the corners. If you came near the fence, they would start shooting,” Gotz said.

Their heads and bodies were shaved, their clothes and luggage taken away, never to be seen again. They had to wear striped uniforms and were driven into barracks.

“We slept on hard boards. No mattress, no straws, nothing. I made myself one year older and said I was 17, because they were killing the younger boys,” Gotz said. “I spent 10 months of my life in that barrack, in total starvation. We got no food. When we came back after a 12-hour shift, we got one lid of parsnip soup and one slice of bread. That was all for a whole day of work.”

Gotz recalled weighing 70 pounds when they were liberated. His father weighed even less.

“For 10 months, I didn’t have a shower. They gave us no washing facilities. We were full of lice, they were giving us diseases. We started to die. I woke up one morning and was shaking my friend to wake up, but he was dead. I carried his body out with another prisoner. I’ve carried more bodies than I can count,” Gotz said.

Life after the war

In April, 1945, Gotz was standing in line to get some soup and bread when the Americans arrived. They were free. Like most others, he ended up in a hospital with his father for six months after liberation.

Within three months, they found out that his mother and aunt were also alive. They were reunited, but Gotz remembers being embarrassed about having two living parents, since almost everyone else was left an orphan.

Gotz graduated as an electrical engineer in 1952 from Witwatersrand University in Johannesburg, South Africa.

“We stayed in Germany because we couldn’t go anywhere. No country wanted us. I was full of hate. When I came out of the hospital, I simply knew I was going to kill some Germans, because that is what they did to us,” Gotz said.

But he eventually admitted to himself, after several months of looking for ways to kill, that he wasn’t in fact a killer.

“I had conversations with myself. Give up that hate, because you can’t live. You’re not thinking about yourself and your future; you’re thinking about them,” Gotz shared. “I decided I can’t hate the whole nation, when only a few of them did bad things. When I gave up hate, I started to live for the first time.”

After many challenges, no official paperwork and a grueling entrance exam, Gotz was admitted to the University of Munich to study electrical engineering. But his family decided to move to Norway, and he had to wait yet again to fulfil his dream of becoming an engineer.

Eventually, the family moved to Rhodesia, now called Zimbabwe, where Gotz learned English before leaving for Johannesburg and finally getting his engineering degree. After graduating, he went back to Zimbabwe and started a radio repair business.

Never one to back down from a challenge, Gotz celebrated Canada’s 150th birthday and his 89th by going skydiving. He says it was a bit scary but lots of fun.

When Gotz was 30, he married his wife Esme in South Africa. They had three children before moving to Canada in 1964. A few years later, Gotz fulfilled his other dream of learning to fly a plane and he became a pilot. At the age of 89, he celebrated Canada’s 150th birthday by jumping out of a plane.

Gotz ended his testimony with a plea for tolerance. “Hatred is a sickness of humanity,” he said. “To hate is a mistake.”

There are two kinds of hate, he said. There is hate for someone who wronged or hurt us in the past. But then there’s hatred for people we don’t even know, those who are different from us – a different skin colour, religion, dress or language.

“I am not asking you to love them,” Gotz told us. “I am asking you to be curious about them. Find out who they are. You will discover a common humanity.”

The memorial ceremony

The virtual event was part of the university’s annual Holocaust Education Week (external link) (HEW) that aims to bring awareness and education to the campus community about the dangers of intolerance and preserve the memory of the Holocaust.

Organized in collaboration with the Ryerson Students’ Union, the evening began with a memorial ceremony that included leaders from various campus student groups lighting a remembrance candle to honour the many communities affected by this dark time in history.

“Holocaust Education Week is a critical opportunity to reflect on topics such as discrimination and antisemitism, and to explore how these themes have both carried out in the past and in the present day,” said Alyssa Lutrin, a third-year student in creative industries, director of Holocaust education and member of the Hillel Ryerson student leadership board.

“It also reinforces solidarity amongst other marginalized groups on campus and demonstrates that in order to grow as a campus community we must recognize each other’s strengths.”

The theme for HEW 2021 was strength and solidarity, encouraging the campus community to understand the lived experiences of survivors, while acknowledging and appreciating the strength of character shown by them during the genocide and to this day.