A new approach to autism

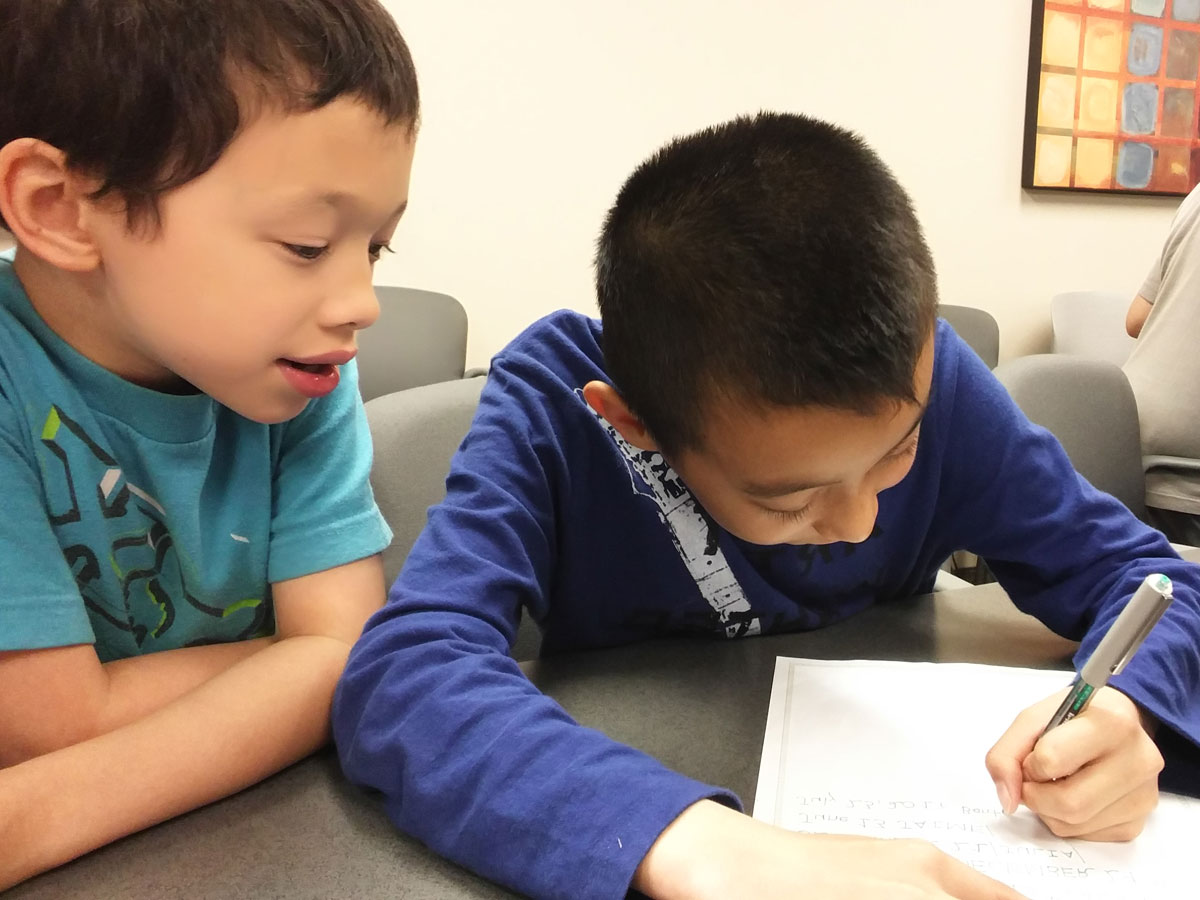

Photo: The “Big Break: Singing and Dancing” camp engages youth living with autism in singing, acting and movement games.

Can drama and music help the emotional responsiveness of children with autism? This is the question behind “Big Break: Singing and Drama” camp, a program that engages preteens and teenagers (ages 10-14) living with autism in singing, acting and movement games.

A collaboration between Ryerson’s SMART Lab (external link) and the Geneva Centre for Autism (external link) , the camp (which ran July 10-14 and August 14-18) emphasizes the core skills of communication (vocal/facial expression, empathy, rhythm, turn-taking, emotion recognition) in a fun, collaborative atmosphere.

The idea was hatched by Lucy McGarry, a 2014 Ryerson PhD graduate in psychology research, whose dissertation studied how imitating a person’s voice and facial expressions could support emotional expression in people with autism. As part of the dissertation, McGarry and psychology professor Frank Russo designed “Big Break: The Acting Game (external link) ”—an app that uses cell-phone cameras to invite users to re-enact emotional speech and song. The app uses face and voice tracking technology to monitor users’ expressions and provide feedback.

Researchers believe that for people with autism, the brain network that maps perception of the world onto action functions differently. “For a typically developing child, if I offer my phone to suggest, ‘Go ahead and use it’—I don’t say anything, but you can read my intent,” said Russo.

“If someone’s moving in a very relaxed manner as opposed to an aggressive manner, you can have insight into their intention by simulating what they’re doing. It’s not the only way we perceive emotion, but it’s an important way, and what our lab has shown is that if you block this simulation mechanism, it becomes harder to read someone else’s emotions. We know that this simulation is not functioning typically in autistic children. We believe that practice with this system is going to rehabilitate the network that’s involved with identifying emotions.”

In addition to research and development support from both levels of government, the project received a donation from Telus through their Community Grant program to help adapt the web-based game for use on a tablet. The app was released in March 2017. After studying use of the app for 13 weeks, McGarry and Russo discovered an increase in social-emotional relations among students who played its games with singing and acting, in comparison to a group that used the game without.

“We think that music might be helpful in that it creates a temporal framework for executing the emotions,” said Russo. “If I was to show you a series of dance moves without music and I said, ‘Repeat them now,’ it would be a really challenging task. But if we did it with a rhythmic or tonal grid, it becomes easier.”

Parallel to the app development, the SMART Lab was in discussion with the Geneva Centre on a program to support emotional communication in children with autism. The app and its findings became a jumping-off point for the camp. Its weeklong July session hosted eight campers on the Ryerson campus, leading them in choir singing, rhythm and drama games, and independent practice with the app.

“We are always looking for opportunities to give our clients an experience they may not otherwise be able to be a part of,” said Renita Paranjape, program director at the Geneva Centre for Autism. “They often don’t get access to camps that have a drama and arts base. For us, it was a win-win to be able to provide access to something like this knowing that the person leading the camp, Sina Fallah, was a really experienced music educator.

“We have the autism expertise, and other people have the music expertise, and the beauty of it was being able to blend the two, and be able to provide our clients with something new and interesting. We always do these things on a trial basis, but we had such a positive experience that we’re in discussion to do something more long-term.”

Neither the camp nor the app is currently an active line of research; Russo hopes to revisit the camp as a more formal study. “The lab-based study was different because it was one-on-one with kids,” said Russo. “We knew that it would be far more complicated getting kids to do group activities, so we started small. What we’re trying to do is figure out what exercises work, and what do we do when there’s disruption in the group.”

“Big Break: The Acting Game” is available in the App Store (external link) . For more information on the SMART Lab, visit its website (external link) .