Revisiting the Flávio story

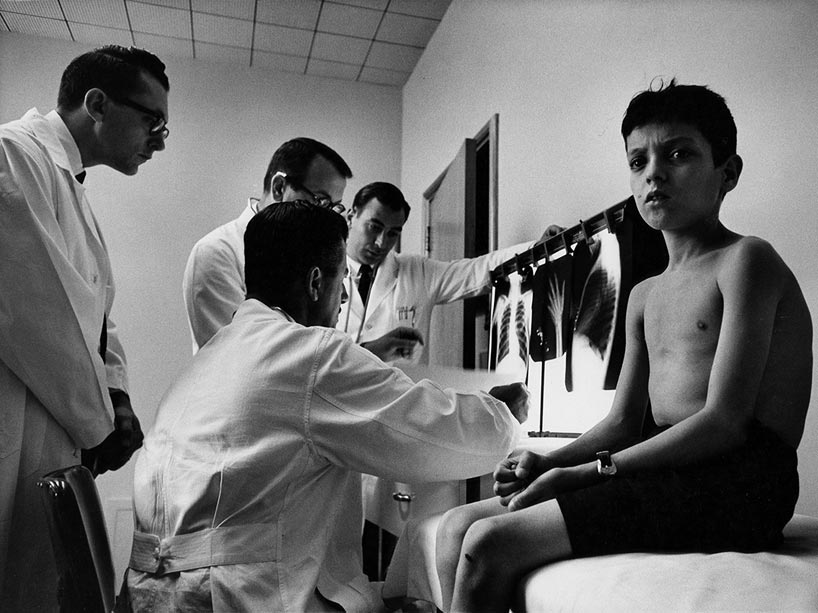

Photo: Carl Iwasaki, Untitled, Denver, Colorado, 1961. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation.

In June 1961, Life magazine published a photo essay about a poor family in Rio de Janeiro that became an immediate sensation. Titled “Freedom’s Fearful Foe: Poverty,” the story was set in a poor community neighbouring a wealthy Brazilian enclave, and introduced Americans to Flávio da Silva, a 12-year-old boy suffering from severe asthma. Flávio’s story inspired an outpouring of support: thousands of letters and nearly $30,000 in donations (equivalent to nearly $250,000 today), which led the magazine to launch a “rescue” effort, resettling the family and paying Flávio’s medical bills.

It was the right story in the right magazine at the right time, and it had the right photographer: Gordon Parks, a musician, novelist, filmmaker (he directed Shaft), and one of the most important photojournalists of the 20th century. A pioneering Black photographer in a time when segregation was still law, his camera captured everything from movie stars to fashion shows to inner-city poverty to the Civil Rights Movement. Flávio’s story would become his most important photo essay.

The Ryerson Image Centre is revisiting this seminal moment with “Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story,” (external link) the centrepiece exhibition of its fall season. The exhibition, co-curated by Ryerson Image Centre director Paul Roth and Amanda Knox (of the J. Paul Getty Museum), highlights Parks’ striking photographs, but also explores the cultural context that made them possible, and features extensive input from the now-grown Flávio.

We spoke to Paul Roth about Gordon Parks, Flávio, and a unique moment in American history…

Why is now the time to revisit the Flávio story?

There are a couple of reasons. One of them was specific to the photographer. Gordon Parks was in his lifetime a very famous photographer—he was the first Black photographer for Life Magazine, and he was also the first Black film director at a major Hollywood studio. He’s been dead now several years, but a lot of his projects are getting a second look, and I’m part of that: I’m on the advisory to the Gordon Parks Foundation. From my perspective, I wanted to work on this project because it’s the most complicated and interesting story that he worked on—not just in the story he told about Flávio for Life magazine, but also the story of what happened as a result of those photographs being published. It was one of the most important, if not the most important, episodes of his entire career as a photographer.

The second reason is the story of poverty, which was really important in at the time, is still very relevant. Even if you specifically look at Brazil, which is where this story was told in 1961, it’s a very important moment to assess Brazilian poverty. Brazil is a country in crisis right now. It’s a really rich country in many ways—a very sophisticated country, and one of the largest countries in the world—but it is also beset by internal divisions. The country is going through a terrible austerity program right now that has stripped money from social services that benefit people like Flávio, and also from the cultural sector—the biggest museum in Brazil just burned down. It’s very upsetting, and yet it’s an extraordinary country in so many ways, and a lot of those dichotomies are present in this story.

Flávio is still alive as well. As a final reason, I thought it was important to tell the story in a comprehensive way while Flávio was still alive so that he could be part of this story. Flávio was never really invited to be part of the telling of the story. He was always the subject of the story. I thought it would be really interesting to get him on the record in this moment of his life while he’s still thinking about it. It’s been an interesting road for him to become a famous person—famous for being poor; famous for being the symbol of suffering. One of the most interesting parts of this has been going and finding Flávio in Brazil and figuring out a way to do this that involved him.

What is his perspective on this now? Does he feel good about it?

It’s complicated. He feels good about it in some ways. He mostly feels as though it doesn’t really matter how he feels about it—it happened to him. He was 12 years old when it happened, and it was an emergency—he was suffering from asthma and had no medical care, and there was a sense that he was going to die quite soon. But the effects of it have been tough for him. He moved to the United States and spent two years there and desperately wanted to stay. He was a 14-year-old boy who went from an absolute state of destitution in a terrible slum with a very difficult family situation, who went to live in a middle-class environment in the United States where he was lavished with attention, and he naturally really enjoyed that and desperately wanted to stay. At the end of the two years, he was denied what he wanted, and he’s had to deal with that ever since. So, every time Gordon would revisit him, or any time a reporter would come, or even this time when I came to talk to him, he’s always reminded that he wants to go back to the United States. He knows that he can’t live in the U.S. anymore, and this was all long ago, but he never really got to go back.

And it’s still happening to him, in a way. Every once in a while, someone will come and ask him the same questions over again, so he feels a little trapped. You know that movie Groundhog Day? It’s a little like that—he has to relive it again and again and again for one person after another, this time for museum curators. We had to negotiate with him to get his involvement. And we wanted to—we didn’t just want to ask for his involvement, we wanted to compensate him for it.

Photo: Gordon Parks, Flavio Feeds Zacarias, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1961, gelatin silver print. Courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation.

How much did he and Gordon Parks stay in touch?

It was situational. They wrote letters to each other occasionally; they talked on the phone every few years. Gordon visited Flávio twice after his childhood—once in the mid-1970s, and once in the late-1990s, just a few years before Gordon died. They were always bonded spiritually by their experience—they felt very warmly to each other.

It’s difficult to image a photo essay like this, and a story like Flávio’s, provoking the same outpouring of support today. What were the historical circumstances that made this possible?

I think a lot of this was related to the optimism that people had in the United States to John F. Kennedy. The photo essay appeared in a very specific political context: it was part of a series of articles designed to drive public support for John F. Kennedy’s policy towards Latin America. He was a still a new president—there was a lot of excitement about his presidency, and there was this very strong feeling of optimism about two different aspects of his policy. One was his anti-communism, which was critical to him getting elected—he basically had to appear to be as anti-communist as his opponents. And also, his warmth and humanism—a kind-of liberal humanism. It was an interesting hybrid, and his Latin American policy fit that hybrid. In very simple terms, it was: we can keep Latin America from going communist by being better to Latin America than we’ve been before, and therefore they will have no reason to turn to communism.

This photo essay appeared at precisely the right moment at precisely the right magazine, and Gordon was precisely the right photographer. It generated tremendous empathy towards this family, and the clearest sense we have is that the public—independently of one another, but spontaneously—decided to send money in to collectively save this family. I say “collectively,” but it was the decisions of individuals.

Life magazine was trying to promote this Kennedy policy, and they thought this would be a good microcosm of that policy. “Let’s take all the money, and we will go as representatives of our readers. We will try to save this policy.” You’re right, I really don’t think it would happen today, but I think the conditions were perfect at that moment.

The media landscape is so different today, too. It’s hard to imagine something like Life—a magazine that everybody reads.

We see little versions of it in the U.S. still—almost like remnants of that way of thinking. For example, CNN has some annual award that they give to heroes, and it’s a similar thing: the idea of the identification of the large news organization with a set of ideals. But it’s only a reminder of the power and reach that Life magazine had at the time, which was just off the charts.

What was it about Gordon Parks’ visual eye that lent itself to this assignment?

First of all, it was pretty far along in his career. He was almost ready to become a filmmaker—and his very first film, in fact, was a follow-up to the Flávio story. We’re going to be showing it in the gallery: an 18-minute film that’s half-documentary, half-children’s film.

I think that he was a very mature image-maker by this point. He was very famous. He was a storyteller by nature, and he was a creative figure in many different arenas. In 1961 he actually left the staff of Life Magazine and was so valuable to them that they hired him back as a freelancer for major projects. They hired him specifically for that visual sense, which was optimized for this kind of story. He was a dramatic image-maker; he knew how to work in difficult conditions; and also, he was an empathetic figure. The people that he photographed trusted him and felt very warmly towards him, and gave him the opportunity to photograph them in a way that they wouldn’t let any other person do. People would be very vulnerable, and they would let him make images that were very romantic. That’s really the advantage Gordon had. It wasn’t just that he was a great image-maker—it was also that he could make images that were deeply romantic.

*

Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story runs September 12 to December 9 at the Ryerson Image Centre with an opening party from 6-8 p.m.