Impacts of federal dental policies on Indigenous peoples

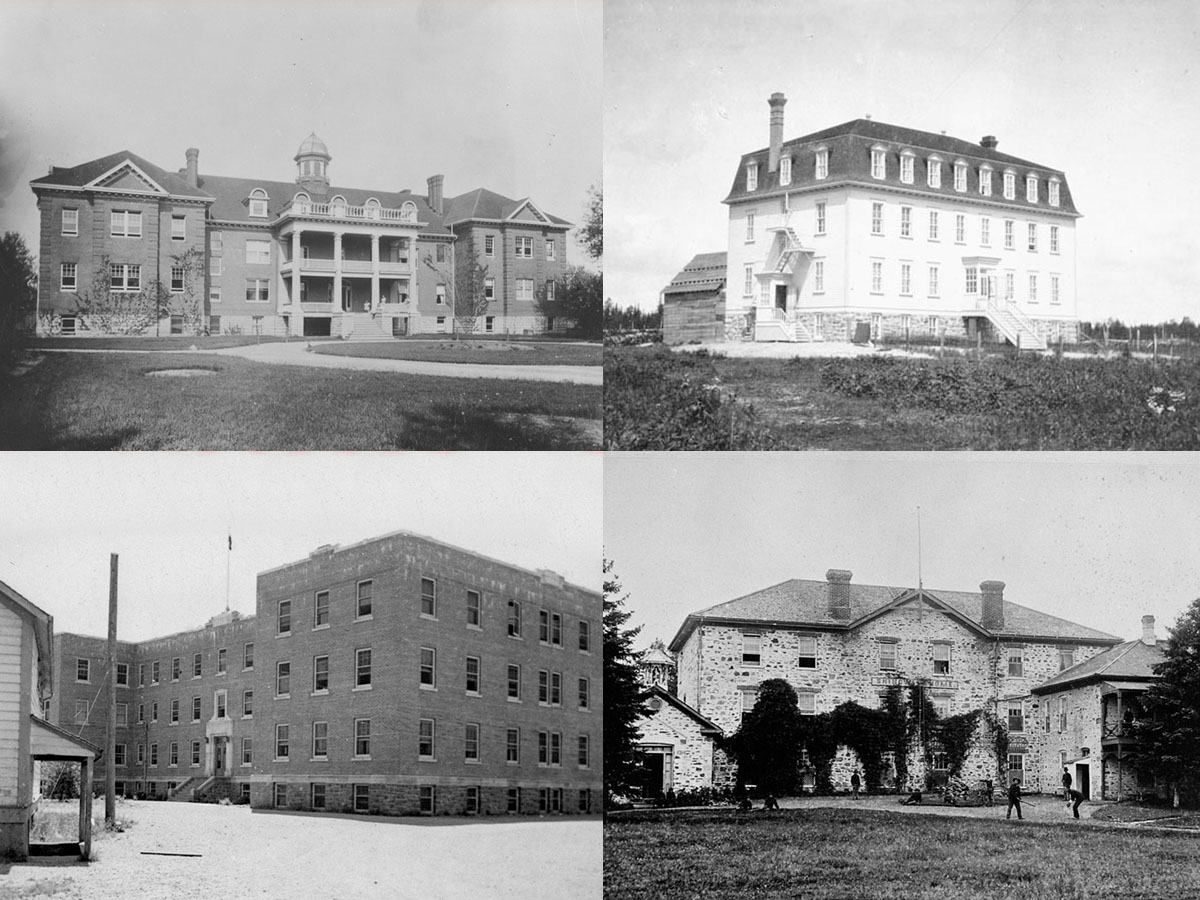

Indigenous people have faced negative and lasting impacts from federal dental policies enacted at residential schools and on reserves between 1945 and 1980, shows research by history professor Ian Mosby. Photos retrieved from the Library and Archives Canada.

By combining the testimony of Indigenous peoples and archival research, a Ryerson researcher is bringing to light how federal dental care policies have had a negative and lasting impact on Indigenous peoples across Canada.

History professor Ian Mosby started researching federal dental care policies and the treatments provided to Indigenous people after he was approached by residential school survivors and their relatives. He’d been invited to speak in a number of communities throughout Canada after publishing research in 2013 on the history of large-scale nutrition experiments conducted in residential schools. In speaking with professor Mosby, individuals wondered about their own experiences, asking about the medical treatments they experienced at school, which included dental procedures.

“They were really horrific. Often people described having multiple tooth extractions done without anesthetic,” he said. Rather than fillings, teeth would often be removed, but dentures wouldn’t be funded.

Professor Mosby teamed up with professor Catherine Carstairs, a University of Guelph historian of dentistry and oral health care, to research the answers to the questions he’d been asked. They sought to figure out what happened with Indigenous peoples and dentistry in residential schools, on reserves and at dentist visits, and they published their findings in a recent Canadian Historical Review article (external link, opens in new window) that focused on the years between 1945 and 1980. “There are some commonalities. Indigenous people in Canada face much higher levels of oral health problems than the Canadian population as a whole,” professor Mosby said. While the explanation frequently discussed by federal policy-makers and researchers is a “nutrition transition” between traditional diets and modern eating habits, he found that reasoning problematic.

The deep dive into government archives, including publicly available records and records received through access to information requests, uncovered the large impact fiscal policy had on the types of care provided. “What we found was that the type of dental care being offered by the federal government to Indigenous peoples between 1945 and 1980 was always done as cheaply as possible. That was always the first administrative decision,” said professor Mosby. The care was often provided by dentists-in-training or federal dentists who were incentivized to turn to procedures like extractions before fillings or other less extreme procedures.

As a result of these fiscally austere dental care policies, many Indigenous people have had a lifetime of problems, from self-esteem issues to malnutrition due to being unable to chew food properly. The experiences have also left many with trauma and fear of going to a dentist or doctor, professor Mosby said. The policies aren't all in the past. Professor Mosby points to a recent case in which an Indigenous child needed braces for pain mitigation (external link, opens in new window) . Instead of providing the funds for orthodontic treatment, the federal government spent over $100,000 fighting the family in court.

Professor Mosby’s research into medical experiments is ongoing as he undertakes the detective archival work, and he’ll report the findings to the communities first. His methodology continues to be to take the experiences he hears about and, working with communities he’s been approached by, digging into records and documents.

“When you start to do historical research by placing a priority on listening to what Indigenous peoples say are their research priorities and believing their testimony, you quickly find records showing that, indeed, the things they’ve been saying for decades about their experiences are true,” said professor Mosby. “None of this should come as a surprise to anyone, especially in the aftermath of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. But, wherever I go, non-Indigenous people ask me, why didn’t they know about any of this? And the answer, frustratingly, is that they need to start listening.”

Professor Mosby’s ongoing research is supported in part by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. The dental history research conducted by professor Mosby and professor Carstairs was supported by the AMS History of Medicine Project Grant from the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation.

Photo information:

Top left: Mohawk Institute, view of the school façade, Brantford, unknown date. (image file) Available online (external link, opens in new window) .

Top right: Fort Frances Indian Residential School (St. Margaret's Indian Residential School), a view of the school, Fort Frances [1907–1908]. (image file) Available online. (external link, opens in new window)

Bottom left: Alberni Indian Residential School, exterior view, Port Alberni, June 1942. (image file) Available online. (external link, opens in new window)

Bottom right: Shingwauk Indian Residential School, boys playing baseball on the lawn in front of the school, Sault Ste. Marie, ca. 1885. (image file) Available online. (external link, opens in new window)

Related links: