Rural Studio Launches Country Culture Lab Publication

Tell us more about your experiences with Rural Studio and its publication Country Culture Lab (external link) , and how we can learn from the "countryside".

Dimitri Papatheodorou (DP): I think it was a great entry point for students to study rural communities; hopefully, it will continue to grow so that we can better understand and contribute to different aspects of the rural condition. Along with George Kapelos’ congruent rural studio last winter, these were the first attempts at researching and designing for the countryside at our school.

I think we really want to encourage a discourse around mindful development with regards to the countryside; what can we do as students of architecture to enhance the discourse around architectural literacy and advocacy? How can we learn, exchange, and solve complex problems? We explore ecology, natural heritage, the environment with regards to sites that have history, beauty, and quality. If you surround these unique aspects with urban sprawl, you're not picking up on those qualities that people love. Over the last year or so, we've seen people moving into rural spaces - whether it's because of affordability, more space, nature, or the confluence of COVID-19 and working remotely from home.

We looked at sustainability from a myriad of aspects, whether that's cultural, technological, form finding and building, land development, job creation and so on. It's not just about the architecture. What's important is that architecture students understand the cultural implications of the workplace they are working in. It’s not just about creating forms, it’s much deeper than that. It’s not just about being able to design well, or beautiful buildings or objects.

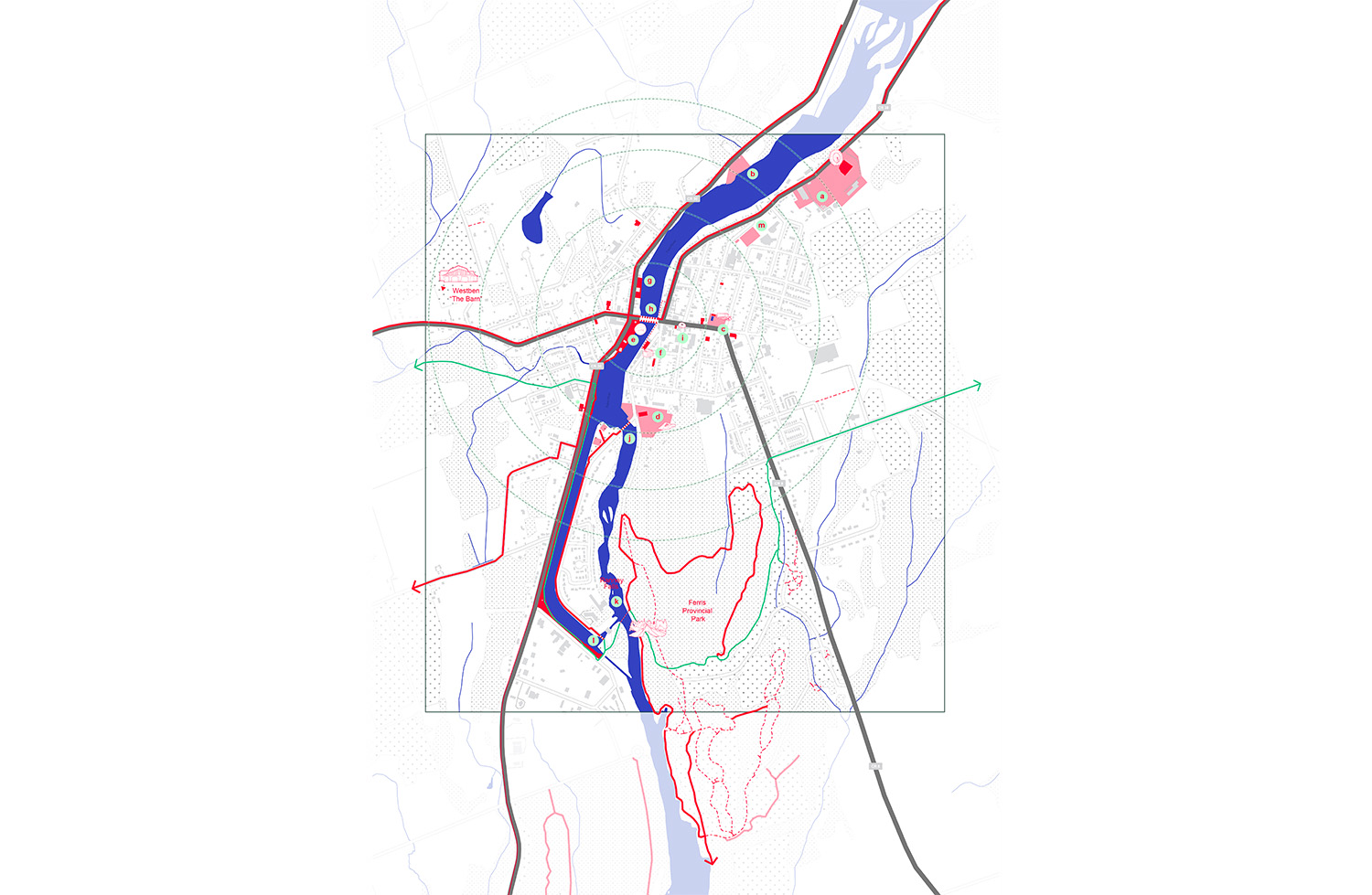

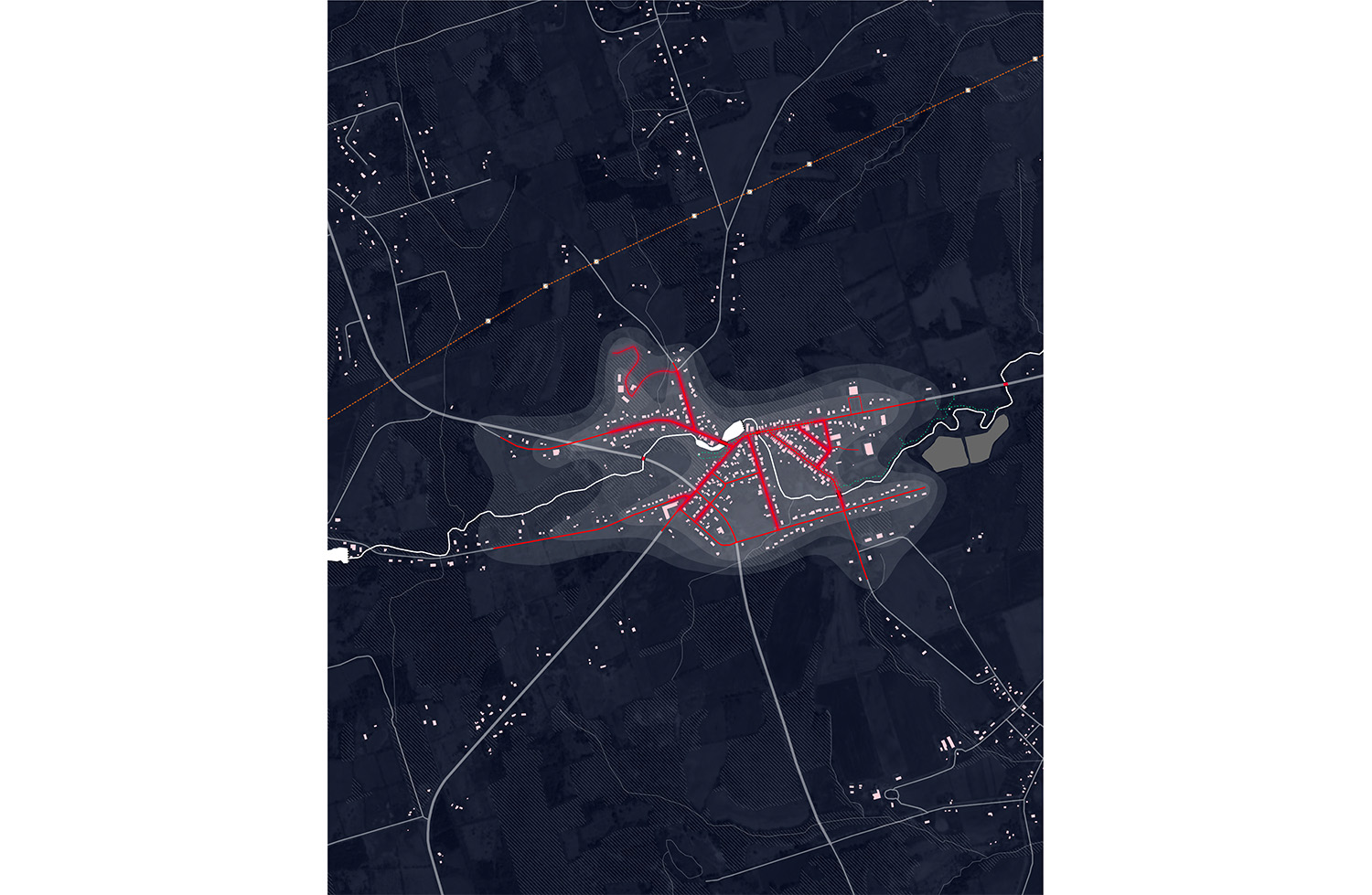

Liane Werdina (LW): We conducted a lot of high level research, whereas most studio projects have you just jumping right in. Most of us were not well acquainted with the towns, so we ended up peeling back layers, researching the rural countryside and the three towns. Mapping exercises (whether it was social or economic data) enabled us to take a layered approach to understanding each town. This deeper level of planning and research I believe better meets the needs of the rural countryside. There are so many different members of the community like urban planners, artists, residents, community members. Our crits became open forums where the community would just have a conversation with us. Most of the time, the community told us what they needed, or had their own ideas of what they wanted in their communities. It really felt like an open dialogue. So before we started designing anything, we were building on this kind of level of research.

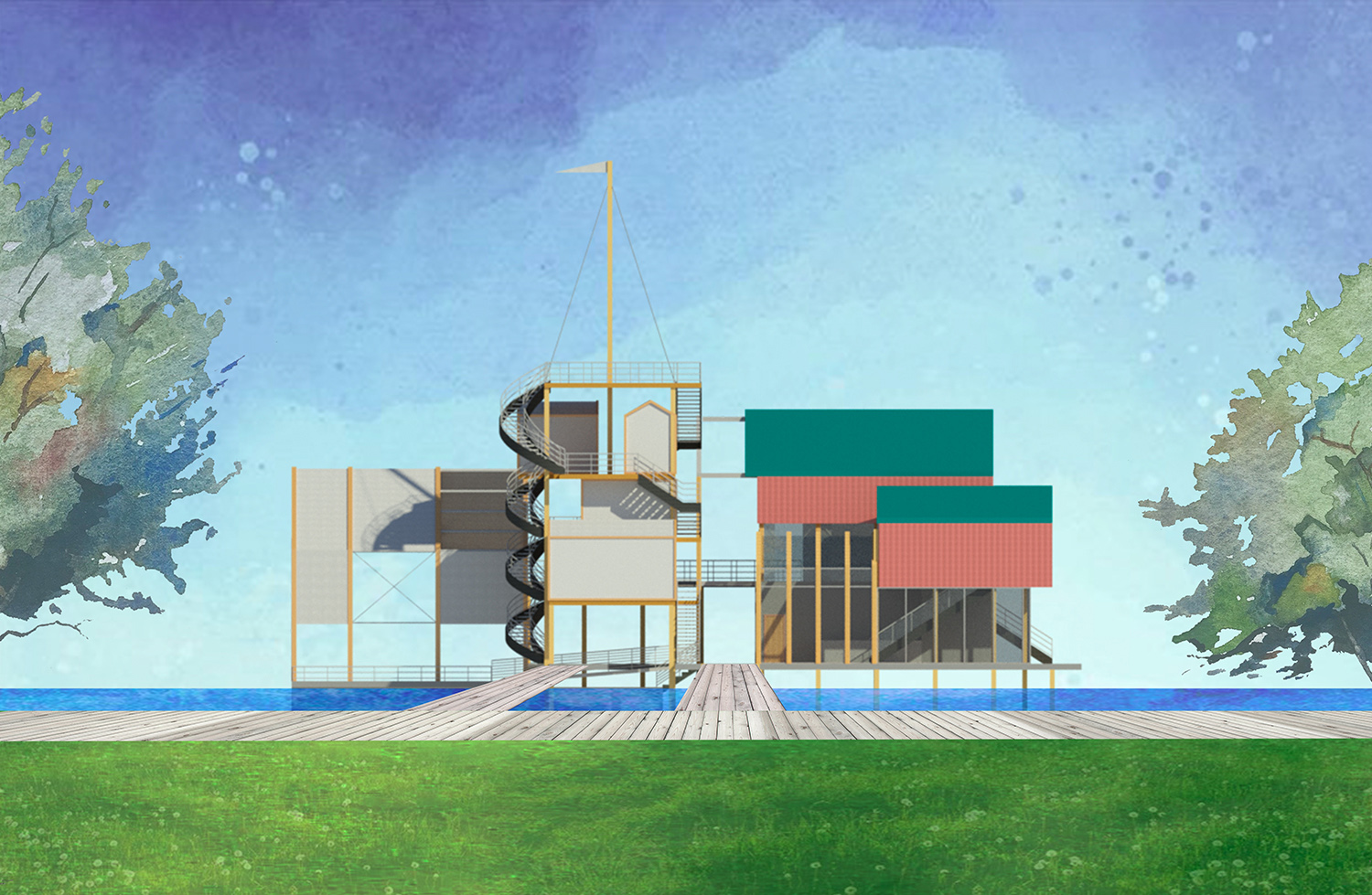

For the "ideology of dwelling" component, most of us designed our dwellings in relation to a specific artist or craftsperson - for example, a ceramicist in relation to neighbours. In the countryside, your next door neighbour is not a condo. We're now at a much smaller, more intimate scale, which means any design decision we make is incredibly impactful - we have to give a lot of consideration to how that dwelling relates to the town and to each other’s projects. No one would locate their project on a site without thinking about it in relation to someone else's. It really ties into what Dimitri said about understanding needs and catering to the people who actually live there.

DP: The work was in relation, the key word being relational. We weren’t drawing property lines, we were designing 3d spaces so that houses and buildings were not conceived of as islands. In the country you often don't really know where one property begins and the other ends.

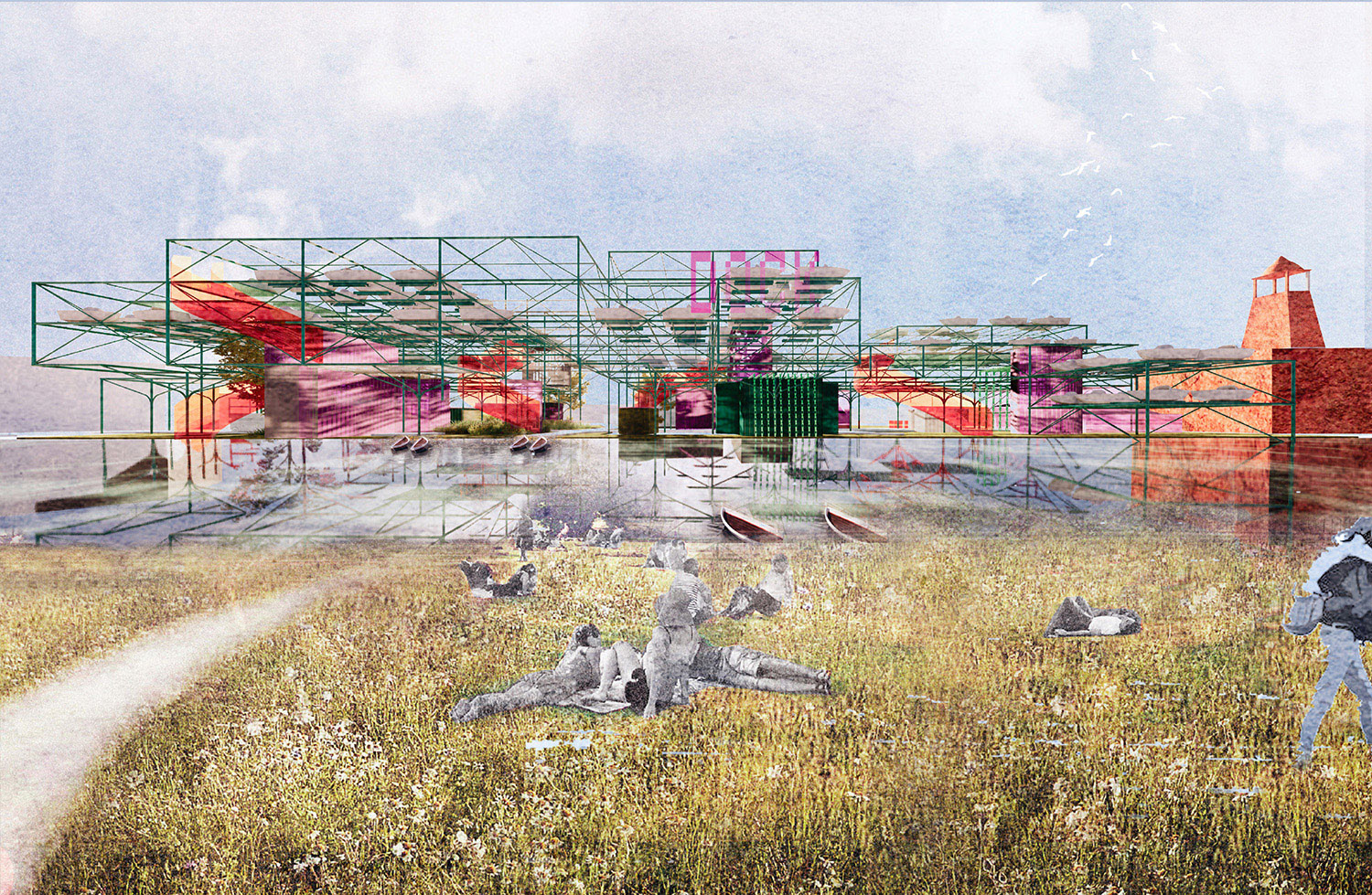

Sophie Twarog (ST): The first thing that came to my mind when you were both talking was placemaking. That was the overall goal of it from my experience. To bring some type of a personal quality that had maybe been forgotten over time with different generations leaving and an ageing population. What was unique was we also got to design our own programming based on our own experiences and interests.

DP: Things are quite sensitive with local communities. It's all about building relationships - our critique of the political climate was primarily a critique of development - in that everything is political. Development for whom? I have to say I was surprised and delighted that these communities had such a large queer presence.

One of the identities that is emerging for these towns is arts and culture. The other communities, such as Campbellford, are all about farming and services. They are all part of one municipality. And of course, they all figure into settler culture (such as through the cottaging industry, for example). We spoke at length about not just further quantifying and commodifying the land from a development perspective but how we can build on these different identities and layer on top of them instead of erasure; colonizing is about erasure. We felt it was important to create a safe space for these communities. By reading, mapping, reflecting, talking, we were able to think through the regional and bi-regional in relation to the global. One of the essays we referred to is one written from an eco-feminist perspective: essentially, you can't take resources from one region of the world (when it's labour or natural resources) and make a beautiful place here with them. Placemaking cannot happen at the expense of other places. We need to build on local ecologies that are working and point out things that aren’t working. Otherwise, the suburbs will invade, and people will be stuck in traffic for hours on sprawling highways unless things change.

Authenticity is really about relating to local narratives and storytelling.

LW: I believe "Shadow Places and the Politics of Dwelling" by Val Plumwood, is the essay he was referring to. This reading, which we did early on, touches on bioregionalism and ecofeminism. Kristen Tsoukas's dwelling project is a great example of this, by rethinking what dwelling meant and really deconstructing the kitchen environment. We had freedom over how we chose to interpret texts. A lot of the housing projects were co-housing projects, so there is an attempt to strip back more colonial ways of living. Yours is like that as well, right Sophie? In terms of co-housing?

ST: I think everyone was exploring co-housing in some form. There were different models of ownership.

DP: A lot of the project was about sharing the land. I think there's a different attitude towards land in these places - and it's also reflected in the sentiments of students. When you’re young you think about equity and fairness all the time, and we were working with a group of students who predominantly identified as women - and everyone identified as an immigrant or first generation. This really brought all sorts of interesting ideas into the mix.

One of the biggest lessons I wanted students to learn is the relationship between theory and practice - we can talk the talk as much as we want, but it isn't real until it lands in the community, and until real people are engaged in whatever work we’re doing. A lot of projects we focus on are urban. But we wanted to engage the community in a more meaningful sense by really testing our ideas. We usually just scrape the surface when it comes to engagement - not knowing the country required us to engage, or we’re just "flying in". The class really ends up being a dialogue between real case studies and literature on rural development. I think we really won't be able to elevate the discourse of the built environment in rural settings unless we actually engage those communities. I feel like a very relevant question these days is how do you address the lack of cultural interest in the built environment?

LW: This notion of testing ideas which you just mentioned is something I really appreciated and took away from the studio. Many projects may not look provocative or appear to be doing something outside the norm or unique, but I think they do when they are examined in relation to one another. Moreover, when we listened to community needs, we knew we didn't have to design something super wild and intense—some projects were small scale interventions or building on something that was already there. In a community where every part of the town is cherished, it can be a challenge to propose something outside the norm - it forces you to rethink the program, rethinking dwelling, cemeteries, schools, for example. We have to be mindful about how we approach people and test different ideas in a new site. It's something I really appreciated and learned from.

DP: If we look at the hotel project in Hastings - it's very strange looking. To most architecture journals, it wouldn’t seem exciting, but it is radical for the community. And, I would say the studio is radical even though it doesn’t look radical.

ST: We were starting to dip our toes into participatory design.

DP: Authenticity is really about relating to local narratives and storytelling. We are flipping the Heideggerian notion of authenticity on its back - which makes me think of the metaphor of the turtle. Dwelling and placemaking is a fluid condition. It isn't a singular authenticity or identity that we are aiming for, but a reinterpretation of this Heideggerian notion.