Narrowing the Housing Price Gap Between the Suburbs and Downtown Toronto: Demand or Supply Driven in the Future?

By: Frank Clayton

September 15, 2022

(PDF file) Print-friendly version available

Summary

Research from the Bank of Canada (external link) supports CUR's findings that the lack of supply of affordable ground-related houses in more central locations results in buyers moving to more fringe areas within the Toronto urban region in search of affordable housing. This out-flow started before the pandemic hit in March 2020 but accelerated as more people worked from home. As a result, many households wanted more space than more centrally located apartments offered. Combined with a shortage of new ground-related houses, the result is that prices of ground-related housing in the Toronto area suburbs are approaching those of more centrally located accommodation.

The land use planning system leads to the underproduction of single-detached, semi-detached and even townhouses compared to market demand for these housing types. Further, the planning system is not incentivizing the production of "missing middle" housing like back-to-back townhouses, stacked townhouses, triplexes, quadruplexes and other low-rise apartment configurations.

Without a substantive rise in the number of "missing middle" housing units built more centrally, the population will continue to move farther afield to find less expensive ground-related housing, resulting in longer commutes. As prices for ground-related housing rise in more central locations because of a limited supply, more households will move further away from employment centres to find housing they can afford, which will push up prices in these locations.

Findings of Bank of Canada research into housing price trends within 15 metropolitan regions

Here are the four verbatim findings of the Bank of Canada study authored by Louis Morel:

- As the bid rent theory predicts, house prices tend to be lower the greater the distance from downtown;

- Before the pandemic, the price gap between houses in the suburbs and those downtown was closing slowly but steadily;

- This house price gap narrowed faster during the pandemic, consistent with a preference shift toward more living space; and

- If the preference shift is temporary, house prices in the suburbs could face downward pressure. This could be especially true if the construction of new houses in suburban areas were to increase significantly in anticipation of local demand continuing to rise.1

These findings were based upon an econometric analysis using the following data sets:

- Teranet-National Bank housing price data by forward sortation area (the first three digits of postal codes) to 80 kilometres from the city centre in 15 major urban regions covering the period from 2014 to 2021; and

- Price data for the sales of all residential houses, from single-detached homes to condominium apartments.

The analysis findings are summarized in two charts in the Bank of Canada's paper (see below).

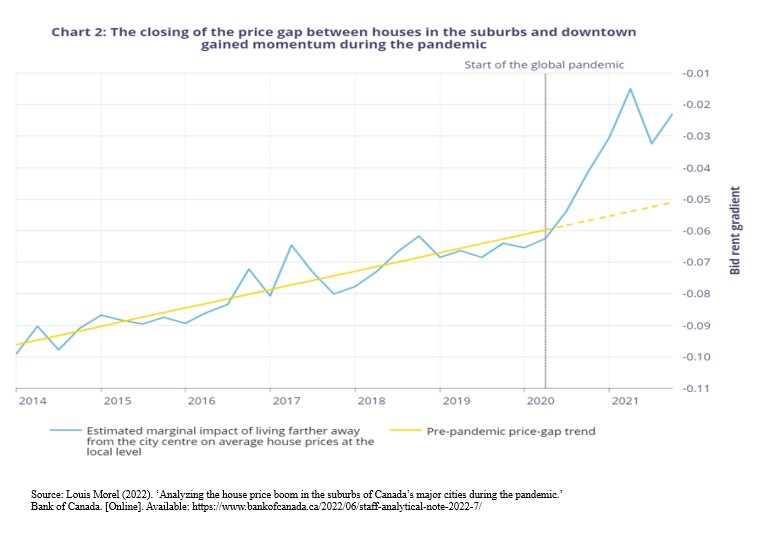

The price gap between housing in the suburbs and the downtown, 2014-2021

The following chart shows the narrowing of the price gap between 2014 and 2019 and its acceleration in 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic. It also estimates that the price-gap narrowing trend during 2014-2019 would have continued in 2020 and 2021 if the pandemic had not occurred, but to a lesser degree.

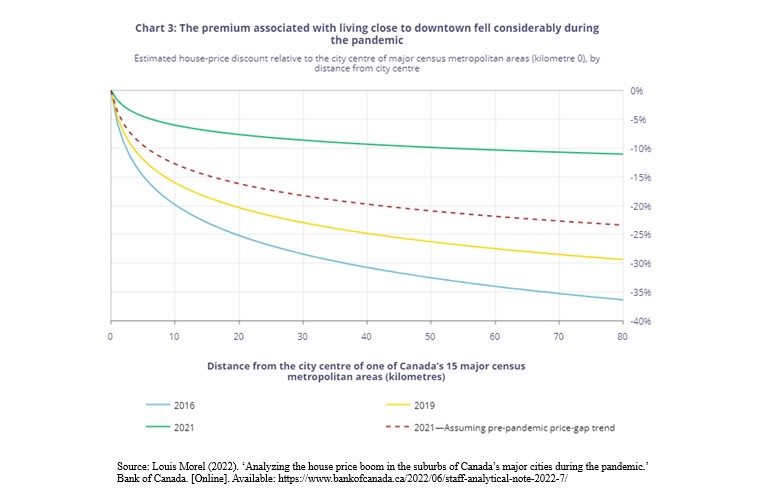

Price gap by distance (up to 80 km) from the downtown, 2016, 2019 and 2021

The chart below shows: (a) the average estimated decline in housing prices for each kilometre up to 80 kilometres relative to the downtown of the urban regions (the price gradient); (b) how the price gradient shifted in favour of the suburbs between 2016 and 2019 with an acceleration between 2019 and 2021; and (c) the estimated price-gap trend in 2021 if the pandemic did not happen.

The author, Louis Morel, informed us that the licensing agreement with Teranet-National Bank prevented him from releasing results for individual urban regions like Toronto. However, he did share with us that: "for the Toronto area, results were robust and very similar to the national figures, and if anything, more pronounced in terms of the shift observed in the gradient during the pandemic".2

This means that the price gap lines in the Bank of Canada's Chart 3 can be used to approximate what has been occurring in the Toronto urban region.

Using the data in the chart to illustrate and referring to the data for similar homes downtown and 50 kilometres from downtown (the suburbs):

- Home prices in 2016 were typically 33% lower in the suburbs than in central Toronto;

- By 2019, the price differential had fallen to 26%;

- During the pandemic (2021), the price gap fell precipitously to a small 10%; and

- If the pandemic had not happened, the price gap would have been a larger 21% in 2021.

What the data show is that the prices of suburban homes have been rising faster than centrally located homes, a trend which accelerated during the pandemic.

Role of demand vs. supply factors and future spatial housing price differences

The root of the dramatic price escalation in the Toronto urban region is that the new housing supply has responded only sluggishly to the robust underlying demand generated by immigration and shifts in the population's age distribution. Moreover, affordability has been made worse by the land use planning regime imposed on the Toronto urban region by the Province in the mid-2000s. This land use planning regime curtailed the construction of ground-related housing (singles, semis, and townhouses) on greenfield land. At the same time, it did not incentivize the building of “missing middle” housing in existing low-density residential neighbourhoods. These include townhouses, back-to-back townhouses, stacked townhouses and other forms of low-rise apartments, including triplexes and quadruplexes.

In our view, the pre-pandemic price-gap trend showing a narrowing of prices between the Toronto area suburbs and central Toronto will likely continue for the foreseeable future. The supply of ground-related and “missing middle” housing types will continue to lag demand. In the short term, however, there will be a downward shift in the green 2021 line in Chart 2 as housing prices soften more in the suburbs as some pandemic-inspired demand shifts back to more central locations.

Our reasoning for concluding the longer-term term trend will be a continued narrowing of the gap between suburban housing prices and prices in more central locations is as follows:

- There was and will be a hearty demand for ground-related housing within an 80+ km radius of central Toronto due to robust immigration, shifts in the age cohorts of the population and intrinsic housing preferences

Forecasts prepared by CUR and by Hemson Consulting detail the robust growth in households resulting from large immigration inflows and the aging of the population as Millennials and Generation Xers move from their parents' houses. The Hemson Consulting forecasts imply that the demand for housing in the current decade will be stronger than in the last decade.3 According to Hemson Consulting, the annual growth in households in the Greater Golden Horseshoe (“GGH”) will average 71,000 per year during 2021-2031, up 42% from 50,000 during the previous decade.

CUR researchers monitoring demographic patterns within the Toronto urban region note the net intra-provincial population losses from the Greater Toronto Area (“GTA”), including Toronto and Mississauga, to the fringe of the GGH and beyond. A significant cause of this out-flow is the desire to find more affordable ground-related housing.4 A recent CUR paper concluded that recent homebuyers and intending homebuyers in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (“GTHA") continue to have a strong innate preference for ground-related houses, especially single-detached houses. Indeed, many recent first-time buyers have purchased a ground-related home.5

- There has been a significant shortfall in the supply of new housing in the Toronto region, especially of ground-related housing

It is now increasingly accepted that the country, and Ontario in particular, has been underproducing new housing, which is a primary cause of the widespread affordability crunch. CMHC, in a recent study, estimated that by 2030, Ontario would need more than a million houses beyond the number planned to accommodate household growth and bring affordability back to what it was in the early 2000s.6

CMHC did not disaggregate the housing shortage by type of unit. However, housing economist Will Dunning has estimated housing shortages by unit type and census metropolitan area. For example, for the Toronto census metropolitan area over the 15 years ending 2020/21, Dunning estimates a shortfall in new housing production of 89,189 units and that the projected shortfall will consist entirely of single-detached and semi-detached houses.7

- The responsiveness of new housing supply to increases in demand and prices is low in the Toronto urban region

New housing differs from many goods and services in that one of its critical components is supplied through a highly regulated planning approvals process rather than the private market. In many cases, the planning process is subject to significant political influence. When housing demand picks up, there is no mechanism to ensure the supply of ready-to-go sites with all planning approvals and servicing is ready to accommodate the demand. As a result, there is a low responsiveness of new housing supply to demand and price signals – supply is thus said to be inelastic. Due to the length of time for the approvals process, there is a lag in the time it takes for the supply to respond to price signals.

Studies by CMHC and the Bank of Canada demonstrate the lack of responsiveness of new housing supply to price signals in the Toronto region. CMHC estimated price elasticities in five urban regions and found that the Vancouver and Toronto urban regions had relatively low-price elasticities.8 In addition, a recent Bank of Canada study estimated housing supply elasticities in a large number of census metropolitan areas. It concluded Toronto has the fourth lowest price elasticity.7

- The combination of steady demand and a sizable shortfall of supply has severely reduced the affordability of ground-related houses

The aggregate affordability measure released quarterly by RBC Economics is now at a record high for housing unaffordability in the Toronto urban region, exceeding the previous high reached in the late 1980s.10 The average-priced MLS single-detached house sold has surpassed the later 1980s, while condominium apartments are still more affordable than in this earlier period.

The longer-term trend in reduced affordability of single-detached houses since the mid-2000s is much more pronounced than that for condominium apartments, according to RBC. The failure of the housing supply system to respond sufficiently or on a timely basis to accommodate the growth in demand for additional ground-related houses is the primary cause of the affordability deterioration.

- There will continue to be a shortfall in new ground-related housing over the next 30 years to accommodate household growth, let alone reduce past housing supply shortfalls and improve affordability

The housing shortage in the Toronto urban region will continue for two reasons. First, under provincial guidance (the “Growth Plan”), municipalities are forecasting housing and land requirements for 30 years ending 2051, sufficient to meet the expected growth in demand but not to reduce past shortages.11 Second, compared to a market-based scenario, the planning-oriented forecasts call for a reduction in the number of single-and semi-detached houses built to be offset mainly through apartments rather than townhouses. The shift is most pronounced in Hamilton, where the market-based need is for about 80% ground-related homes, and the City is instead planning to build about 80% apartments.

A previous CUR paper examining the housing requirement forecasts of the 905 regions around Toronto details this incongruity between the supply and demand for ground-related housing.12

- Households will continue to move farther from central Toronto to find affordable ground-related houses, which will result in a more dispersed population and community-based jobs than there would be otherwise

Several CUR papers have addressed the implications of the continued underproduction of ground-related housing in the Toronto urban region. A recent paper dealing with the topic of sprawl summarizes the implications of a significant shortage of ground-related housing:

It is time to stop referring to all greenfield development as sprawl. Ottawa, for example, in its preparation for the latest version of its official plan, clearly distinguishes the type of greenfield development occurring there from sprawl. Failure to acknowledge this distinction in the GTHA will result in higher housing costs and longer commutes. Curtailing the supply of greenfield ground-related homes will raise the prices of these units, shifting demand for existing homes which will raise prices and/or have potential purchasers opt for ground-related homes further afield, which may increase commuting times.13

Conclusion

Research from the Bank of Canada supports CUR's findings that the lack of supply of affordable ground-related houses in more central locations results in buyers moving to more fringe areas within the Toronto urban region in search of affordable housing. This out-flow started before the pandemic hit in March 2020 but accelerated as more people worked from home. As a result, many households wanted more space than more centrally located apartments offered. Combined with a shortage of new ground-related houses, the result is that prices of ground-related housing in the Toronto area suburbs are approaching that of more centrally located accommodation.

The land use planning system leads to the underproduction of single-detached, semi-detached and even townhouses compared to market demand for these housing types. Further, the planning system is not incentivizing the production of "missing middle" housing like back-to-back townhouses, stacked townhouses, triplexes, quadruplexes and other low-rise apartment configurations.

Without a substantive rise in the number of "missing middle" housing units built more centrally, the population will continue to move farther afield to find less expensive ground-related housing, resulting in longer commutes. As prices for ground-related housing rise in more central locations because of a limited supply, more households will move further away from employment centres to find housing they can afford, which will push up prices in these locations.

Sources:

[1] Louis Morel (2022). ‘Analyzing the house price boom in the suburbs of Canada’s major cities during the pandemic.’ Bank of Canada. [Online]. Available: https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2022/06/staff-analytical-note-2022-7/ (external link)

[2] Email to Frank Clayton from Louis Morel, Senior Policy Advisor and Editor of the Financial System Review dated July 11, 2022.

[3] Diana Petramala and Frank Clayton (2020). ‘Upbeat Outlook for the GTHA Economy to Stoke Home Prices and Rents: Housing Affordability to Remain Challenged.’ Centre for Urban Research and Land Development. [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://www.torontomu.ca/content/dam/centre-urban-research-land-development/pdfs/Projects/TRREB/CUR_Upbeat_Outlook_for_GTA_Economy_to_Continue_to_Stoke_Home_Prices_and_Rents.pdf; and Hemson Consulting Ltd. (2020). ‘Greater Golden Horseshoe: Growth Forecasts to 2051. Technical Report prepared for the Ministry of Municipal Affair.’ [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://www.hemson.com/wp-content/ uploads/2020/08/HEMSON-GGH-Growth-Outlook-Report-26Aug20.pdf.

[4] Diana Petramala and Frank Clayton (2022). ‘Affordability Issues, Not the Pandemic, Drive Population from the City of Toronto and Peel Region.’ Centre for Urban Research and Land Development. [Online]. Available: https://www.torontomu.ca/centre-urban-research-land-development/blog/blogentry62/

[5] Frank Clayton (2022). ‘What Kinds of Housing Are Homebuyers or Intending Homebuyers in the GTHA Choosing?’ Centre for Urban Research and Land Development. [Online]. Available: https://www.torontomu.ca/content/dam/centre-urban-research-land-development/CUR_Preference_Homebuyers_Intending_Hombuyers_GTHA_June_2022.pdf.

[6] CMHC (2022). ‘Canada’s Housing Supply Shortages: estimating what is needed to solve Canada’s housing affordability crisis by 2030.’ [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://assets.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/sites/cmhc/professional/housing-markets-data-and-research/housing-research/research-reports/2022/housing-shortages-canada-solving-affordability-crisis-en.pdf?rev=88308aef-f14a-4dbb-b692-6ebbddcd79a0 (external link) .

[7] Will Dunning Inc. (2022). ‘Housing Production in Canada Has Fallen Far Short of the Needs of Our Growing Population.’ [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://www.wdunning.com/_files/ugd/ddda71_b3ac6b482e344ac7a5cb2046ac976458.pdf (external link) .

[8] CMHC (2018). "Examining Escalating House Prices in Large Canadian Metropolitan Centers." [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://assets.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/sf/project/cmhc/pdfs/content/en/69262.pdf?rev=15f4d0e4-a2e6-4aab-bb31-f4d88b5b17e4 (external link)

[9] Nuno Paixao (2021). ‘Housing Supply Elasticities.’ Bank of Canada. [Online]. Available: https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2021/09/staff-analytical-note-2021-21/ (external link) .

[10] RBC Economics (2022). ‘Housing Trends and Affordability: Canadian home buyers face least affordable market in a generation.’ [Online]. Available: https://royal-bank-of-canada-2124.docs.contently.com/v/housing-trends-and-affordability-june2022 (external link) .

[11] A recent expert panel report in B.C, concludes there is a need for an “affordability adjustment” to account for past undersupply. See Canada-British Columbia Expert Panel on the Future of Housing Supply and Affordability (2021). “Opening Doors: Unlocking Housing Supply for Affordability, Final Report.” [Online] Available: (PDF file) https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/588/2021/06/Opening-Doors_BC-Expert-Panel_Final-Report_Jun16.pdf (external link)

[12] Frank Clayton and Graeme Paton (2022). ‘GTHA 2021-2051 Land Needs Forecasts Lack Viable Alternatives to Single-Detached Houses.’ Centre for Urban Research and Land Development. [Online]. Available: https://www.torontomu.ca/content/dam/centre-urban-research-land-development/CUR_Land_Needs_GGH_and_Missing_Middle_Aug.2022.pdf.

[13] Frank Clayton and David Amborski (2022). ‘Is All Greenfield Development in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area Sprawl? A Resounding No.’ Centre for Urban Research and Land Development. [Online]. Available: https://www.torontomu.ca/content/ryerson/centre-urban-research-land-development/blog/blogentry68.html.

Frank Clayton, Ph.D., is Senior Research Fellow at Toronto Metropolitan University’s Centre for Urban Research and Land Development (CUR) in Toronto.